You are in total control??

Understanding Politics of Design

YOU ARE IN TOTAL CONTROL. At least, that’s the story you’ve been told. You get to choose what you share online, whom you share it with, and how it is shared. Technology companies are bending over backward to give you more perceived control over your personal information. The common narrative is that victims of privacy breaches only have themselves to blame. But reality is: all the focus on control distracts you from what really affects your privacy in the modern age. The most important decisions regarding your privacy were made long before you picked up your phone or walked out of your house. It is all in the design.

Design affects how something is perceived, functions, and is used. Technologies are great examples of the power of design. Design could be used to leverage better users’ expectation.

Even when design is not shaping our perceptions of a technology, it is in the background, shaping what happens to us. Users usually cannot tell what kinds of personal information the websites and apps they visit are collecting. Every website and mobile application collects some kind of arguably personal data, such as Internet Protocol (IP) addresses, browser type, and even browsing activities. Modern information technologies are specially designed to collect more, more, more.

This article highlights how design affects your privacy and it is written in three distinct points:

1. Design is everywhere.

There are two particular kinds of consumer technologies: those used by people and those used directly upon them. Most of the technologies we use mediate our experiences.

- Browsers, mobile apps, social media, messaging software — are media through which we find and consume information and communicate with others.

- Surveillance technologies like license plate readers, drone, and facial recognition software are used upon us. We don’t interact with these kinds of technologies, yet they have a profound effect on our privacy.

You can see the impact of design on our privacy almost everywhere you look. In the physical world, doors, walls, closed-circuit television, modesty panels for lecture hall tables, and any countless number of other design features shape our notions of privacy.

Philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham designed the panopticon as a prison comprising a circular structure with a guard tower at its center, thus allowing a single guard (or a small group of guards) to observe all the prisoners at any given time.

This design has become a metaphor, pioneered by philosopher Michel Foucault, for the modern surveillance state and the cause of surveillance paranoia.

Privacy-relevant design is everywhere. It’s part of every action we take using our photos, laptops and tablets. It’s also a force upon us we interact in this physical world. The best way to spot privacy-relevant design is to look for the ways in which technologies signal information about their function or operation or how technologies make tasks easier or harder transaction costs. Signals and transaction costs shape our mental models of how technologies work and form the constraints that guide our behavior in particular ways.

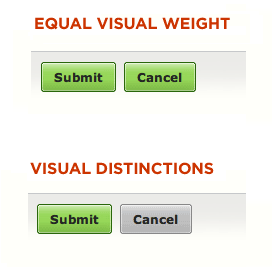

Signals can also modulate transaction costs themselves. Weak signals burden users with the cost of finding more information. Strong signals reduce the burden of retrieving information. For example, buttons with labels send signals to users that make the decision as to when to press the button easier.

Other examples are:

2. Design is power.

Power has been defined as, “the capacity or ability to direct or influence the behavior of others or the course of events.” (taken from Oxford Dictionary) Given how design can shape our perceptions, behavior and values, power and design often feel like synonym.

Every design decision makes a certain reality more or less likely. Designers therefore wield a certain amount of control over others. Because people react to signals and constraints in predictable ways, the design of consumer technologies can manipulate its users into making certain decisions. Design affects our perceptions of relationship and risk. It also affects our behavior: when design makes things easy, we are more likely to act; when design makes things hard, we are more likely to give up and look elsewhere. The power of design makes it dangerous to ignore.

Economic professor Richard Thaler and law professor Cass Sunstein have pioneered the concept of “nudging,” which leverages design to improve people’s lives through what Thaler and Sunstein call, “choice architecture.” Choice architects are people who have “the responsibility for organizing the context in which people make decisions.” A nudge is “any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. Designers and engineers are choice architects.

Design shapes our privacy perceptions, which in turn shape how we use and respond to technologies. Because privacy is so difficult to pin down and the harms are so diverse and often remote, we crave privacy guideline. Design gives it to us.

Alessandro Acquisti, Laura Brandimarte, and George Lowenstein explains the our vulnerability to design and external forces that shape how we disclose personal information and make choices regarding our privacy.

These are:

- People are uncertain about the nature of privacy trade-offs and about what kinds of trade-offs they prefer. Information asymmetries keep people from properly assessing risk, and even when privacy consequences are clear, people are uncertain about their preferences.

- Our privacy policies are almost entirely context dependent. As Acquisti note, “The same person can, in some situations, be oblivious to, but in other situations be acutely concerned about, issues of privacy.”

- Our privacy preferences are incredibly malleable — that is, they are subject to influence from others who have better insights into what will make us act.

Our uncertainty, malleability and dependence upon context all work together. We might be so dependent upon context because of how uncertain wee are about the outcomes of sharing personal information. We need lot of clues to give us a hint as to what to do. And our privacy preferences and behaviors are malleable and subject to influence because we are so dependent upon context. Because our privacy intuitions are so malleable, we are vulnerable to those who would manipulate context to their own advantage.

Coming back to design. Norman’s theory of good design is a function of mental mapping, technical and normative constraints, and affordances. The concept of affordances — the fundamental properties that determine how a thing can be used — is useful because it gives us a framework for understanding how people interpret and then interact with an object or environment.

In other words, the facilitation of a particular action or behaviour by an artefact’s design to a particular user is known as an ‘affordance’.

Affordances can be negative and positive, depending upon how they are perceived, and they can also be seen as subject to change. Whether an affordance is true or false, perceptible or hidden, also affects how people interact with objects and environments.

3. Design is Political.

The misconception that design is neutral. Design is never neutral. It is political. It should be a key part of our informational policy.

Evidence-based user experience research, training, and consulting” firm Nielsen Norman Group published a report on best practices to consider when designing websites for children. But they forgot to consider how design impacts the well-being of children.

Habits are formed around the usability of a product; if an app or website makes it easy to complete a task, users are likely to do it more often than not. Usability advocates often treat this as an inherently good quality; by and large every business wants their products to be easier rather than more difficult to use.

Design is moving past the stage in the evolution of the craft when we can safely consider its practice to be neutral, to be without inherent virtue or without inherent vice. At some point, making it easier and easier to pull the handle on a slot machine reflects on the intentions of the designer of that experience. If design is going to fulfill the potential practitioners have routinely claimed for years–that it’s a transformative force that improves people’s lives–designers have to own up to how it’s used.

Design is always political, because design is about changing a material world. It’s about including certain people and excluding others, whether by means of functional design, pricing, or accessibility.

— Professor Alison J. Clarke, Director of the Victor J. Papanek Foundation at the University of Applied Arts Vienna.

Design is not only about making things look beautiful, designing forms, driving consumerism, or creating objects.

In the end, I would like to say:

Design Should be Policy

Because design can allocate power to people and industries, it is inherently political. The law can recognize the role that design plays in shaping our privacy expectations and reality. Design and architecture affect every choice we make.

When people make decisions, they do so against a background consisting of choice architecture. A cafeteria has a design, and the design will affect what people choose to eat. The same is true of websites. Department stores have architectures, and they can be designed so as to promote or discourage certain choices by shoppers (such as leaving without making a purchase.) This architecture will affect people’s choices even if the effect is not intended by designers. Another example, people have a tendency to buy things they encounter first, so even if you are not trying to sell a lot of a sweater vests, putting them at the entrance to your store will probably move more vests than if you tuck them away in some corner.

We cannot avoid choice architecture. As Sunstein notes, “Human beings (or dogs or cats or horses) cannot wish [choice architecture] away. Any store has a design; some products are seen first, and others are not. A website has a design, and that design will affect how users will navigate the site and how long they will stay. When lawmakers and judges ignore design they implicitly endorse the status quo and the unchecked use of power.

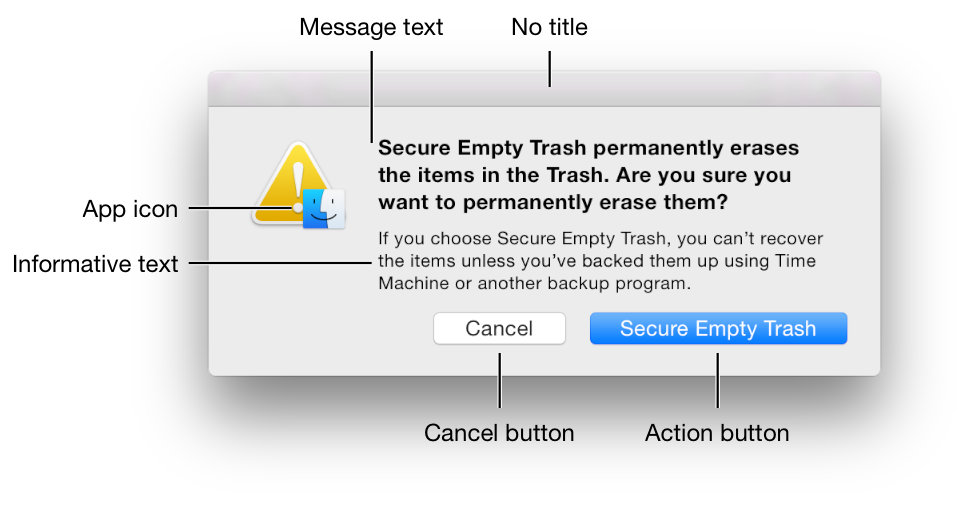

Consider default rules and settings, which are the preselected choices that will take effect anytime a person does nothing or fails to select an option. For example the on / off toggle button that is so common on our smartphones.

There are only two possible choices here: on or off. Designers must choose to preselect the default position for the button. This choice cannot be avoided, beacuse even some halfway choice in a binary decision would basically function as off. Because we know defaults are sticky and it would take the user’s scarce resources of time and attention to change the settings, the default decision reflects a value. If the default for location tracking and sharing were set to on, we should expect the exact location of many more phone users to be tracked and shared. Many of us might not mind, but political dissidents and those seeking refuge from domestic abuse be jeopardized by this default. And even in the case of domestic help, where there location is tracked in the gated community.

The danger of defaults is acute when people are unaware of them or when the panel of selections looks like this cascading array of options. The default for many social services is set to maximize sharing at the expense of discretion. According to a 2015 study from Kaspersky Lab, 28% percent of social media users neglect privacy settings and leave all of their posts, photos, and videos accessible to the public.

There are hundreds of buttons under the hood of our technologies. Each default settings affects our choices.

And we users are severely outmatched. Technology users operate as isolated individuals making decisions about things we don’t know much about, like the risk of disclosing information and agreeing to confusing legalese.

Lawmakers must acknowledge that the law inevitably influences design. Once lawmakers, policy creators and judges realize that choice architecture is unavoidable and that the design of systems has moral implications, they have a choice to make:

- They can keep the status quo and basically ignore the design of technologies when addressing privacy law, or

- They can confront the important ways design shapes morally relevant outcomes.

Designers are always engaged in some kind of political activity. It may not be big party politics or representing a particular standpoint, but what they give to the world has consequences.

It’s not just a linear relationship in which designers create things and we consume them. It’s a symbiotic relationship. What we as consumers or as citizens begin to demand and envisage has to be fed back into the design process. We are all responsible for the stuff that surrounds us. It isn’t just the problem of corporation A and designer B. It’s a whole cosmology of wants and needs, and we really need to address that. None of us is innocent in this process. We’re all implicated.

References.

- Foucault, M., 2012. Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Vintage.

- Lyon, D., 1994. The electronic eye: The rise of surveillance society. U of Minnesota Press.

- Thaler, R.H. and Sunstein, C.R., 2009. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Penguin.

- Sustein, C.R., 2015. The ethics of nudging. Yale J. on Reg., 32, p.413.

- Acquisti, A., Brandimarte, L. and Loewenstein, G., 2015. Privacy and human behavior in the age of information. Science, 347(6221), pp.509–514.

- Norman, D.A., 1999. Affordance, conventions, and design. interactions, 6(3), pp.38–43.

- Gibson, J.J., 1977. The theory of affordances. Hilldale, USA, 1, p.2.

- Hartzog, W. and Stutzman, F., 2013. The case for online obscurity. Calif. L. Rev., 101, p.1.